The story of Israel begins not with a nation, but with a man who would not let go of God. In the midnight struggle by the Jabbok River, Jacob wrestled with the divine until daybreak, and there received a new name: Israel — “the one who strives with God” (Genesis 32:28). The name became a lasting emblem of Israel’s struggle with God, a history-long wrestle through which God unveils to the nations the truth of who He is.

The blessings and transformation Jacob encountered at the Jabbok River served as a reaffirmation of the covenant God made to Abraham and Isaac. From Jacob/Israel’s sons came twelve tribes, “the tribes of Israel” (Genesis 49:28) woven together into a people set apart.

A Jew, an Israelite, and a Hebrew Walk Into the Bible…

Many centuries later, during Solomon’s reign, the once-united kingdom fractured: the northern tribes called themselves Israel, while Judah remained in the south. Later, the north fell to Assyria; the south to Babylon. Yet even in exile, the identity of God’s people endured. When they returned, they were called “Jews” — a name derived from Judah, yet encompassing the whole house of Israel. Over time, all twelve streams flowed back into one river, their shared destiny preserved in the people who would carry the covenant forward.

When we speak today of the Jewish people, we are speaking of all the children of Jacob — not merely of Judah (the fourth son of Jacob and Leah and father of the Tribe of Judah), but of Israel in its wholeness: a people who have endured exile, been refined in the crucible of history, and who still bear the name of the one who wrestled with God through the night and refused to release Him.

Recap: The Hebrew word Yehudi (Jew) comes from Yehuda (Judah). At first, it referred to those from the southern kingdom after Solomon’s kingdom was divided. But following the Assyrian exile of Israel in 722 BC (2 Kings 16:6, KJV) and the Babylonian exile of Judah in 586 BC (Ezra 4:12), the term “Jew” took on a broader meaning, describing the survivors from all twelve tribes who returned to rebuild Jerusalem and the Temple. Thus, by the Second Temple period, Jew and Israelite were used interchangeably.

Even older is the term Hebrew (Ivri), used for Abraham (Genesis 14:13) and his descendants. Later, in the New Testament, Paul calls himself a “Hebrew of Hebrews” (Philippians 3:5), “a Jew” (Acts 21:39), and “an Israelite” (Romans 11:1). Thus, these terms often overlap historically; they are not rigidly separated.

The terms “Judah” (Jerusalem area), “Jew” (ethnicity), and “Judaism” (religion) can be confusing because they all come from the same Hebrew root, Y-H-D:

- Yehuda (Judah) is the name of one of Jacob’s sons and the tribe that descended from him. Jerusalem was located within the territory of the tribe of Yehuda (Judah).

- Yehudi (Jew) originally referred specifically to someone from the tribe of Judah. Over time, especially after the exile, it became a broader term for anyone descending from any of the twelve tribes of Israel who identified with the people of Israel.

- Yahadut (Judaism) refers primarily to the religious tradition that, following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 AD, developed under the Pharisees, later known as Rabbinic Judaism. Today, Rabbinic Judaism represents the religious beliefs and practices of roughly a third of Jews worldwide.

Thus, Jewish identity today is a tapestry of lineage, covenant, religion, and culture — not every Jew is strictly from the tribe of Judah, nor does every Jew follow Yahadut — Rabbinic Judaism — the religious system developed after the destruction of the Second Temple. Many Jews identify as secular, cultural, traditional, or follow other Jewish streams (like Reform, Conservative, or Karaite traditions). Some Jews, in rejecting Rabbinic Judaism altogether, come to believe in Jesus. Most Jewish believers today express their faith through a Romanized-Westernized perspective — some become part of the Catholic Church, others have joined Anglican communities, and some align with Protestant traditions (often identifying themselves as “Messianic,” usually Baptist, Calvinist or Pentecostal believers). Yet, some are like me — Jews who believe in Jesus, feel comfortable worshiping across all denominations, yet theologically are not formally part of any specific religious group.

Israel: By Blood or By Covenant?

Some argue Israel is defined not by bloodline but by covenant faithfulness. This has biblical roots: the Torah warns that Israelites who persist in idolatry will be “cut off” (Leviticus 17:4), and the prophets call for “circumcision of the heart” (Deuteronomy 10:16; Jeremiah 4:4). But they never suggest physical descent is meaningless — they assume the people of Israel are physically part of Israel, calling them to live out their calling. Moses and the prophets spoke directly to circumcised Israelites. They never abolished or erased their physical identity as a people, but rather called them to live in harmony with it. Again and again, they urged Israel to “circumcise their hearts” — to align their inner lives with the covenant, not merely to rely on the outward sign of belonging.

The New Testament echoes this prophetic line. Paul writes, “Not all who are descended from Israel are Israel” (Romans 9:6–8), pointing to a faithful remnant within ethnic Israel — not saying Gentiles replace Israel to create a “New Israel,” but highlighting that within Israel, some walk in covenant, others do not.

You can think of it as a majestic lineage: the fact that a prince is a son of a king does not automatically make him a good, kind, or faithful ruler when he becomes king himself. That is why Israel’s prophets were sent — not to abolish that identity, but to hold it accountable. Time and again, Israel’s prophets challenged and encouraged Israel’s leaders to live worthy of their calling. Consider the prophet Nathan, who boldly confronted King David after his sin with Bathsheba, reminding him that even a king stands under God’s covenant authority.

In summary, Israel’s identity has always carried two strands — the blood of Jacob’s sons and the covenant of God’s voice. The prophets never erased Israel’s lineage; they held it accountable, urging the people to “circumcise their hearts” so their lives would match their calling. Paul echoes the same truth (Romans 9:6). Within the nation, some fall away, yet others remain faithful — the remnant who keep the covenant alive (Romans 11:5). Thus, Israel is not replaced, but refined; still chosen, still enduring, yet always summoned to let its outward heritage be joined with inward faith.

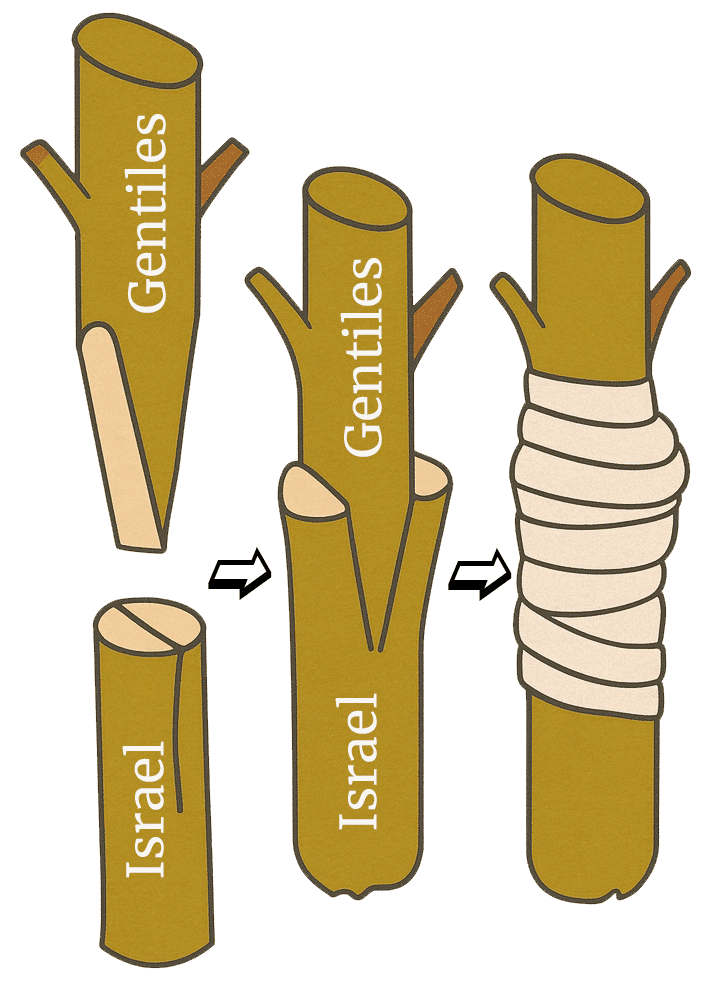

Romans 11 — The Olive Tree: Grafting, Not Replacing

Grafting an olive tree is an ancient agricultural skill used to preserve and strengthen trees. The process involves carefully cutting a branch from one tree and inserting it into a slit in the bark of another. The farmer then binds it tightly so that the sap from the rootstock (the original tree) can flow into the grafted branch. Over time, the two grow together and become one living organism. Though the branch did not originally belong to that tree, it begins to draw life from its roots and eventually produces fruit as if it had always been part of it. Farmers do this for several reasons: sometimes to save an old tree whose natural branches no longer bear well, sometimes to improve the fruit quality by adding a healthier or more fruitful variety, and sometimes to bring new life to a tree that would otherwise be unproductive. In short, grafting is a way of rescuing, restoring, and renewing.

Paul’s olive tree metaphor (Romans 11) is essential to understanding Israel’s role in God’s plan. Just as farmers graft branches into an olive tree so they can draw life from its roots and bear fruit again, Paul shows how God grafts people into His covenant family — giving them new life, purpose, and fruitfulness in Him. Here’s the picture:

- The root and tree = Israel, God’s covenant nation, nourished by the patriarchal promises (Romans 11:16–18; Jeremiah 11:16; Isaiah 11:1).

- Natural branches = ethnic Jews, some faithful, some “broken off” because of unbelief (Romans 11:17, 20). However, this is only temporary as, in the future, the “natural branches be grafted back into their own olive tree” (Romans 11:24).

- Wild branches grafted in = Gentile believers, joined (not replacing) to Israel’s promises through Messiah (Romans 11:17, 24; Ephesians 3:6).

- The remnant = Jewish believers in Jesus, part of the faithful core or “remnant” (Romans 11:5, Kings 19:18).

Christianity = A Jewish Denomination

Throughout history, many Jewish movements and sects have rallied around leaders they believed to be the Messiah. In Paul’s day, during the first century, what we now call “Christianity” was not a separate religion but a Jewish denomination. The earliest followers of Jesus continued to live as Jews, worship in Jewish synagogues, and observe the feasts of Israel. Most of the so‑called “Christian church” were themselves Jewish men and women who believed Jesus was the long‑awaited Messiah. They represented the faithful remnant of Israel.

Furthermore, Paul explicitly warns Gentiles: “Do not consider yourself superior to those other branches… You do not support the root, but the root supports you” (Romans 11:18). Paul’s warning suggests antisemitism was already alive and kicking in his time. Yet, Paul envisioned a time when the natural branches will be grafted back in, leading to reconciliation and much greater blessing to the world (Romans 11:12, 15, 25–26). Paul’s theology is not of replacement but of an enlargement.

Besides, for the natural branches to be grafted back in — it presupposes that Israel must still exist as a distinct people. If the Jewish people had been dissolved or lost their identity, there would be no “natural branches” to restore. The very metaphor assumes continuity: Israel remains, even in unbelief, so that God’s promises may ultimately be fulfilled in them.

The Apostle Paul, grappling with Israel’s unbelief, emphatically rejects the notion that God has replaced or rejected His people:

I ask, then, has God rejected his people? By no means! I myself am an Israelite, a descendant of Abraham, a member of the tribe of Benjamin. God has not rejected his people whom he foreknew.

(Romans 11:1-2)

Paul points to himself (a Jew, an Israelite, a Hebrew) as evidence that God still has a plan for Israel, and he foresees a future redemption for Israel as a whole, calling it a “mystery,” emphasizing that the hardening is partial and temporary (Romans 11:25–26):

I do not want you to be ignorant of this mystery, brothers and sisters, so that you may not be conceited: Israel has experienced a hardening in part until the full number of the Gentiles has come in.

(Romans 11:25)

If “Israel” really meant “the Church” — as some claim — then the verse makes no sense, for it was the Jewish people, not the Church, who experienced a hardening toward Christ.

Paul clearly draws a distinction between two groups: Israel, which is experiencing a temporary hardening, and the Gentiles, who are being brought to faith. Paul teaches that only after the “fullness of the Gentiles” comes in — perhaps implying a future universal conversion — will Israel’s spiritual blindness be lifted. This only makes sense if Israel still exists as a people — otherwise, the apostle’s hope and prophecy would be empty. The very structure of Paul’s argument assumes that Israel endures through history, awaiting its ultimate restoration. Israel is not perfect, and it is fair to criticize her when warranted. But make no mistake: those who seek her destruction — especially Islam — place themselves in direct opposition to God’s plan. (Romans 11:29).

Paul then exults in God’s faithfulness by quoting the prophet: “The Deliverer will come from Zion… and this is My covenant with them…” (Romans 11:26–27). In other words, God is not done with Israel because He swore long ago to be their God. “For the sake of the patriarchs,” Paul says, “they are beloved, for the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable” (Romans 11:29). Here, Paul clearly connects the covenant God made with Israel’s patriarchs to His promises, which he claims are irrevocable.

This reality speaks to both the mind and the heart. To the mind, it reassures us that God’s promises hold together in perfect harmony — His covenant with Israel standing firm, and through it His covenant with the Church and with each believer in Christ. If He has not abandoned His first covenant, then we can trust beyond doubt that He will never abandon the New Covenant sealed in Jesus. To the heart, it unveils God’s fatherly love. Like a devoted parent who may discipline their child but will never cast them away, God’s love endures through our failures. Knowing this fills us with hope — that the One who promised never to leave or forsake Israel will never leave or forsake us (Hebrews 13:5).

But Didn’t Paul Write “Neither Jew Nor Gentile”?

Paul’s famous declaration in Galatians 3:28 has often been misread as teaching that Israel’s unique identity has been erased:

There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus.

(Galatians 3:28)

Some have used this verse as a proof-text for Replacement Theology, claiming that the Church has supplanted Israel. But Paul’s words cannot be twisted in that direction. His concern is not the erasure of God-given identities (after all, males do not cease to be males, nor females to be females), but the removal of barriers that once limited access to God.

For most of human history, the world was ordered by rigid classes and hierarchies — kings and peasants, masters and slaves, male and female, priests and commoners — and the modern idea of equality simply did not exist. In the Second Temple, walls and inscriptions enforced sharp divisions: Jews over Gentiles, men over women, priests over laypeople. Only certain people were permitted to cross the Temple’s barriers and draw near to the inner, ‘holier’ courts. Paul, shaped by this very world, proclaims that in Christ those walls have been torn down. In Him, every believer now has access and stands on equal footing before God — regardless of ethnicity, gender, or religious rank. The identity remains; it is the access that changes.

But equality does not mean sameness. Consider Paul’s phrase, “neither male nor female.” If taken as an abolition of gender, then Paul was the first gender activist, erasing Genesis 1:27 and campaigning for unisex bathrooms two millennia ahead of schedule. Clearly, he meant no such thing. Men remain men, women remain women — but both are equal heirs in Christ.

By the same logic, Jews remain Jews, and Gentiles remain Gentiles. The difference is that inheritance no longer belongs exclusively to one group. The promises flow through the singular “seed” of Abraham — Messiah Jesus (Galatians 3:16). All who belong to Him, Jew or Gentile, share in Abraham’s blessing.

This does not cancel Israel’s role. Paul insists elsewhere that “the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable” (Romans 11:29). Israel remains the root into which Gentile believers are grafted (Romans 11:17–18). Likewise, in Matthew 19:28, Jesus promised the twelve apostles would sit on twelve thrones “judging the twelve tribes of Israel.” Hard to judge Israel’s tribes if Israel no longer exists. The biblical story closes with Israel’s tribes inscribed on the gates of the New Jerusalem (Revelation 21:12). From Genesis to Revelation, Israel is never erased.

Replacement theology collapses under this weight. It confuses equality of access with uniformity of identity, contradicts Paul’s teaching, and undermines God’s faithfulness.

The truth is richer: Galatians 3 announces that the barriers are gone. No one is barred from God’s family table. Jew and Gentile, slave and free, male and female — all are equal heirs, united in Christ. The wall of exclusion is torn down, but the beauty of God’s diverse creation remains.

Unity without erasure — that is Paul’s message to the Galatians.

Against Replacement Theology

Paul, writing decades after Christ’s ascension, still identified himself openly as a Hebrew (Philippians 3:5), an Israelite (Romans 11:1), and a Jew (Acts 21:39). Yet as the Gospel spread among the Gentiles, a tragic distortion emerged: some non-Jewish believers began to boast, imagining themselves as the ‘New Israel,’ as though they had replaced God’s original covenant people — the root itself (Romans 11:16–18). This idea, later formalized into what we now call Replacement Theology, not only ignores Paul’s clear teaching but also severs the Gospel from its Jewish roots.

Replacement Theology — also known as supersessionism — claims the Church has permanently replaced ethnic Israel as God’s people. The phrase “new Israel,” however, appears nowhere in Scripture. Historically, this view dominated much of Western Christianity (both Catholic and Protestant), but Paul’s vision clearly contradicts it.

Paul’s olive tree image is not about cutting down the old tree and planting a new one; it is about grafting, healing, and making one people from both Jew and Gentile in Messiah. Gentile believers are “grafted in among the others” (Romans 11:17) through faith — not replacing the tree itself.

In modern times, the re-establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 has compelled many Christians to reconsider Replacement Theology and rethink the ancient covenants. Israel’s very existence today stands as a living testimony that God’s promises endure. Gentile followers of Jesus are called to recognize that the Jewish people still hold a unique and irreplaceable role in God’s unfolding redemptive plan.

Even the Catholic Church, which for centuries fostered theological hostility toward the Jewish people, publicly shifted its stance in the wake of Israel’s rebirth as a modern state. During the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965), the Church issued Nostra Aetate, a landmark declaration that rejected the charge of collective Jewish guilt for the death of Jesus and affirmed the enduring covenant between God and Israel. Reflecting on that turning point, Pope Francis later wrote:

The Church officially recognizes that the People of Israel continue to be the Chosen People.

(Pope Francis)

This marked a profound departure from centuries of supersessionist thought within the Catholic tradition.

Like it or not, Jesus was — and remains — a Jew. And just as the Jewish roots of the Gospel cannot be erased, neither can the significant future role that Scripture assigns to Israel (Romans 11:15, 25–29). These future promises lose all meaning if there is no longer such a thing as “Israel,” replaced by a so-called non-Jewish “new Israel.”

Here, the image of the Prodigal Son becomes deeply powerful: Israel, though estranged for a time, remains the Father’s beloved child. The Father still stands at the road, arms open, longing for reconciliation. This is precisely Paul’s longing too: “My heart’s desire and prayer to God for the Israelites is that they may be saved” (Romans 10:1). This is not mere wishful thinking on Paul’s part; it echoes God’s own covenant plan and points prophetically to the end of days. Paul unfolds this mystery in the very next chapter:

I want you to understand this mystery, brothers and sisters, so that you may not claim to be wiser than you are: a hardening has come upon part of Israel until the full number of the gentiles has come in. And in this way all Israel will be saved.

(Romans 11:25-26)

In God’s grand design, all nations will eventually join Israel — not geographically or genetically, but spiritually, by forsaking false gods and turning to the God of Israel. In that way, God triumphs, Israel’s calling is fulfilled, and the covenant story reaches its climax. And at the very end, the Jewish people themselves will awaken to confess Yeshua as Messiah. That is game over — the moment of cosmic reconciliation, when “all Israel will be saved.”

Final Thoughts: One Story, Many Branches

Biblical faithfulness calls us to affirm that the Abrahamic covenant has never been revoked. Israel remains Israel, and Gentile believers, through faith, are graciously grafted into something older, deeper, and more enduring. Jesus, the Jewish Messiah, fulfilled Israel’s promises, but His fulfillment does not dissolve God’s covenant with the Jewish people.

In a metaphorical sense, “spiritual Israel” includes non-Jewish followers of Jesus who have been grafted into Israel’s story — just as Ruth the Moabite was when she clung to Naomi’s people and declared, “Your people shall be my people, and your God my God” (Ruth 1:16). But this spiritual belonging does not erase or replace the physical descendants of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Instead, Ruth’s words show us the posture Christians are called to take: to love Israel’s God, to embrace Israel’s people, and in doing so to “provoke them to jealousy” (Romans 11:11) — not by boasting, but by walking humbly in faith, love, and covenant loyalty.

In the end, the Church is not Israel’s replacement but Israel’s enlargement. Unlike Islam, which seeks conquest by the sword and coercion, the God of Israel “conquers” the nations through faith — drawing hearts to Himself in love. His promises still stand, His purposes still unfold, and the day will come when both the natural and the wild branches will glorify Him together in the fullness of redemption.

This was a full chapter from my book, “The Elephant in the Middle East: The Spiritual Battle Christians Often Miss Behind the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict“: